Graphic Novels

One of the best things about being designer, is that everything I see and experience in life can factor into my work.

Recently, I’ve been getting into graphic novels – especially those by Marjane Satrapi, Guy Delisle, and Jason.

As someone with a fine art practice background and interest in non-money making hobbies (such as teaching yoga), I am naturally interested in ways that people cultivate their creative practice while being financially fit. It humbles me to see people with great talent and dedication, stay with the thing they love to do, even if that means trading a bit of financial security.

I came across a 2-year old post by cartoonist Lars Martinson about How to Self-Publish a Graphic Novel in 8 Hard Steps that gives a glimpse into the practical dedication necessary.

Filed under: Uncategorized | Leave a Comment

Making Ideas Happen

Lots of books out there talk about product development methodologies, but not many come from a designer’s point of view.

Lots of books out there talk about product development methodologies, but not many come from a designer’s point of view.

Scott Belsky understands the whims and tendencies of designers, and has advice on how to realize ideas.

In order to execute, the founder and CEO of Behance, says, designers must be able to overcome the creative mind’s tendencies to think of random ideas and actions. Although it might feel unintuitive, it’s necessary to stop thinking and just do the work necessary to finish the piece of work.

Belsky is also an advocate of making ideas public. Desginers may fear that the original idea will be diluted when it is shared to many people. But, the cost of variation from own vision is outweighed by benefits of shared ownership and scalability.

Overall, the book is about structuring the work process to let creative ideas materialize and yield results.

Lots of creative projects and people are mentioned as reference. Benjamin Franklin’s daily routine was simple and disciplined. Ji Lee is said to have worked on eight or more projects in parallel, a number that would require excellent project management skills.

———————————————————————————————————————————————–

- Ji Lee’s portfolio: http://pleaseenjoy.com/

- Benjamin Franklin’s Daily Routine: http://dailyroutines.typepad.com/daily_routines/2007/07/benjamin-frankl.html

- Behance: http://www.behance.net/

Filed under: books | Leave a Comment

A design backlog for your ideas

I’d like to jot down some things I’ve learned over the course of the year as a work newbie. Here’s #4:

4. Create a backlog for all the things you need to do, then prioritize them

At work, my project ran on an Agile development method called Scrum.

Scrum is a methodology for software development, which helps the team get visible, working results every 2~3 weeks.

This method is great for the prototype-driven attitude, where the product needs to work first, and the rest of the details can be tuned.

This method gets products out to the market fast, and works in the software industry where products can be updated after deployment.

Anyways, Scrum comes with predefined rules, and there are even books written about how to carry out this process.

One of the rules that turns out to be useful in general daily life as well as product development, is the use of the Product Backlog.

A backlog is a list of everything you know you have to do, ordered by priority.

Now, this idea of a prioritized list is useful in life, when you have millions of different things swarming around in your head, but together, they just make noise.

1. Get a text-editor, or Post-Its, and write each of your to-do items down as a brain dump.

2. You should be satisfied to have untangled the various ideas in your head

3. Now, order these individual tasks by most to least important.

4. Focus on your life for the next week or two. How much time will you have available to do things on this list?

5. Estimate how long each of your tasks will take.

6. Commit yourself to the top tasks, and don’t commit to more than you have time for.

7. At first, your estimation of tasks might be a bit off, because there’s always the unexpected, or a seemingly simple task may snowball into something big. As time goes by, you will learn how to “chunk” tasks better, into manageable bits.

If you’re at all like me, with a “divergent” though pattern (likes to spread out ideas and brainstorm, but isn’t really good at choosing just one), then this prioritization method can help a lot.

Do you ever get that tingling feeling of adrenaline rushing through your body, when you realize that you’ve set yourself up to do more than you can possibly do in a given amount of time? Well, using the estimation process, you don’t have to feel rushed or nervous about the amount of time you have. I’ve learned that that tingling feeling, no matter how exciting it can feel at times, isn’t a good thing. It usually turns out to be a sign that you won’t be done on time.

Filed under: mindmap, process | Leave a Comment

Tags: agile, process, project management, scheduling, scrum

Made by humans

I’d like to jot down some things I’ve learned over the course of the year as a work newbie. Here’s #3:

3. Don’t underestimate the resources it takes to create the most basic product

Based on my decades-old experience as a consumer, objects simply existed out of the blue.

To elaborate, plastic Happy Meal figurines from McDonald’s originated from the paper bag behind the store counter,

meat at the grocery store came from styrofoam dishes wrapped in Saran Wrap, and

Wonder bread came from a white bag printed with colorful balloons.

As for web sites like Google and Yahoo!, the screens simply existed on my monitor.

And these pages were available within milliseconds of a request.

One of the big discoveries that I made at work was that actual human beings made these digital layouts and pages.

Duh.

Of course, I don’t think I really really believed that these web products existed without human’s creating them. But, I just wasn’t able to imagine the extent to which each pixel and column width is scrutinized and thought over by people poring over their monitors and printouts.

There must be a physical law that proves that things take a tedious amount of time to prepare, and a miniscule amount to devour or consume. If there isn’t, I think I can create one for the product industry.

A typical day of the illustrator guy in my team includes zooming into a 24X4-pixel icon by 2000% and adjusting the opacity of each 1X1 pixel square.

Once, I had a friend call and ask for 100 icon illustrations within the next two days, or sooner, if possible. What experience teaches, is the ability to determine that this request is insane. Experience also grants the confidence to be able to tell that friend, “no. Let’s look into what you’re really asking for.” From a binary mindset, to answer the question, “can it be done, or can’t it?” — one would answer “of course it can be done”. From a design point of view, which requires a qualitative assessment of the work needed, the answer is that “it can’t be done well enough to be worth showing to users. Let’s schedule this properly.”

As part of the design program at Stanford, my class took some contact improv lessons from a dance instructor. He described the body as a filter – the mind runs faster than the body can. And, the limitations of the body filters our thoughts into things that are physically doable. I think of the role of designers is like the body. We filter the sprawling ideas of product managers and ourselves, in order to create tangible things. And while there is a magical part to seeing something materialize, project team members need to be informed that this magic is actually done by humans, and that it takes time.

Filed under: digital, institution | Leave a Comment

Tags: design, project management, scheduling, user experience design

You can negotiate anything

Useful advice on how to make sense of complex negotiating situations. For people who have no clue how to think of negotiations as “games,” this book provides instructions. For example, the important elements to gain an upper hand on are, TIME, KNOWLEDGE, and POWER. You also need to realize that seemingly Official rules were the results of negotiations at some point in time. Thus, you can challenge these official rules when doing so is to your advantage. On the other hand, you can use the power of appearing legit, to your advantage: “See? It’s printed in article 4.3 in this document.” Overall, in general, you need to have an attitude, and believe in your pursuit.

Useful advice on how to make sense of complex negotiating situations. For people who have no clue how to think of negotiations as “games,” this book provides instructions. For example, the important elements to gain an upper hand on are, TIME, KNOWLEDGE, and POWER. You also need to realize that seemingly Official rules were the results of negotiations at some point in time. Thus, you can challenge these official rules when doing so is to your advantage. On the other hand, you can use the power of appearing legit, to your advantage: “See? It’s printed in article 4.3 in this document.” Overall, in general, you need to have an attitude, and believe in your pursuit.

Filed under: books | Leave a Comment

Tags: books, negotiation

I’d like to jot down some things I’ve learned over the course of the year as a work newbie. Here’s #2:

2. Don’t be afraid of awkward silence, when negotiating schedules

When my team started on a project, the engineers and project managers didn’t seem to understand that we needed TIME to design page layouts and modules. They were focused on the functionality, and attention to form-making seemed very weak.

Consequently, we were often asked to do the impossible: “Can you come up with a design for this page, and deliver it ASAP? We’re making this request now, but it’s already late. Can you do it ASAP? The engineers are waiting and the front end coders are without work before you give them something to code.”

It was frustrating as user experience designers, to have to argue for the value of our existence and our rights to a proper schedule.

Still, when it came to negotiating deadlines with other functions in our project team, it was very difficult to give into the pressure of time. It was somehow our fault that we needed time to design things. We knew this atmosphere had to be corrected by educating the whole team about the design process. But, to me as a newbie, it was physically difficult to endure the presence of a roomful of people surrounding my little team, or to withstand a long silence of tension over the phone, if we were setting commitments over a conference call. I was constantly feeling apologetic to everybody about having become the burden and the obstacle to a speedy execution.

One of the best things I learned from my boss is how to handle pressure gracefully. She, my boss, is a composed human being. By nature, she is never rushed or moody. It’s a mystery as to how she never seems to get angry or upset. I once did see her get disappointed over an employee, but never have I seen her visibly emotional.

Anyway, when I first joined her team, the long awkward silences that she created in phone conferences would make me antsy and restless in my chair. Our project manager would be on the other line, overseas, and we’d be sitting in our office with the mute button. The project manager would be asking us to deliver some designs at too tight a deadline, and we would try to get more time. The PM would suggest a date, and we’d just wait for minutes, in silence. (or, we’d be discussing amongst ourselves over the muted speakers) This prolonged silence, with tension, was uncomfortable.

But, by focusing on our needs first and calmly discussing our timeline helped us create the proper designs and deliver results, which everybody was satisfied with at the end. If we had negotiated a schedule that we felt nervous about, then the situation would have only gotten worse.

There are times when I think that user experience design can be better integrated into an agile development process — without us having to be the black swan(or, rather, sheep!) that behaves differently and demands things that the others don’t. But that’s a different story.

According to negotiator Herb Cohen, you should not to be the first to break the awkward silence. The other side will finally have to say something, thus giving you valuable information that may give you an edge in the negotiation. The scheduling part for a project is the stage where you make your bed before lying in it. If it’s not done right, the whole thing can go awry. To do it right, you need to negotiate with your teammates, and sometimes you need to protect your team by not giving into emotional pressures. Enduring long awkward silences in the process, takes courage and self-confidence.

Filed under: digital, institution, process | Leave a Comment

Tags: agile, design, internet, negotiation, user experience design

It just might have been bad luck

Being jobless straight out of school could make you feel like you're out on the streets wandering in the cold. (photo from flickr user Runs with Scissors)

I’d like to jot down some things I’ve learned over the course of the year as a work newbie. Here’s #1:

1. It’s not just your fault. Getting hired takes luck

Applying to a bunch of jobs to no avail right after college took a hit on my morale and self esteem at first. It was also humbling and made me reassess the value I’d thought I was adding to society.

“Nobody needs me! I can just go to that corner and disappear quietly. Nobody will notice,” said my inner wino. Smart people told me to think proactively, by coming up with ways to make people realize that they need my services. Then, I could plant the idea in the employers heads, Inception style. But, I honestly couldn’t imagine a way. Especially not if I wanted to be enjoying whatever I ended up doing for a living.

I decided, I was to blame for my own unemployment — I hadn’t studied one of the majors known for success in the job world. Instead, I had chosen the major that is typically known to lead perfectly capable people into starvation– fine art. Consequently, my skills needed tweaking to fit the needs of a company. I also had been applying to various jobs only half-heartedly. In fact, there wasn’t a job description anywhere that I was thrilled about, and I wasn’t about to mask my skepticism with bursting enthusiasm and passion in an interview.

Fast forward a few years, and what I’ve realized is that the difficulty of finding a full-time job straight out of university wasn’t just my problem. It was so many other people’s problem at the time that it became a national problem. And a problem that the president had to address. And it was called a “high national unemployment rate.” If so many people have the same problem, it’s time to wonder if something external is the cause. In hindsight, I probably deserved just about 70% of the blame for not having been able to find a job (for the reasons mentioned above). Thirty percent of the blame would go to bad timing. When you feel like battering yourself for your own misfortune, listen and see if your country’s economy telling you, “it’s not you, it’s me.” And this is the first reason why getting employed takes good luck.

The new intern in our design team just started work last week. We picked her out from over a hundred applicants. We interviewed five out of the pool. Then, we debated which one of the top two should get the final call. And the selection was made based on lots of small details. Either applicant would have added value to the team, and if our team had had the luxury of supporting two interns, we probably would have.

All five interviewees had impressive portfolios. If our team had relied more on visual rendering skills rather than communication skills and attitude, we might have chosen one of the other applicants. But my team currently focuses a lot more on communication than just visual rendering skills. The applicants couldn’t have known this in advance, because the official job description isn’t as detailed to that point. So by these considerations, we selected our current intern.

In selecting an intern, we as the employer had the upper hand. If, as Herb Cohen outlines in You can negotiate anything, that the three keys to winning a negotiation are TIME, POWER, and INFORMATION, we definitely had the upper hand over applicants in all aspects. We had more information than they, even if they’d researched our company and products. We weren’t limited to certain time pressures, whereas many of the applicants were graduating from school soon and were in a hurry to compete for job openings in a tight market. Finally, we definitely had the power to choose one out of many applicants, whereas, the applicants had their shots more limited.

This typical story of an intern getting picked is a case of good matchmaking, in which both sides met at the right time with matching goals and needs.

Yes, hiring and being hired is more like matchmaking, rather than the job-seeking side trying to satisfy some golden rule in order to be allowed through the royal gates. Some may have known this all along, but the revelation has been fascinating to me. Especially, if you’ve been going to school for long, there may always have been an official goal marker to tell you if you’ve done a good enough job.

But work is different, and it takes some luck to find the right match.

Filed under: institution, process | Leave a Comment

Tags: advice, employment, hiring, job, out of school, unemployment, work

First published in 1937, this book is still on the featured lists of bookstores off and onine. For about a year, I had kept off reading this book because I was afraid the title would make me look like a loser — “Look at that forlorn dork who needs a book to teach her how to make friends, haha!” After a year since getting to know the title, and after building some self-esteem and confidence, I finally bought the volume and started reading.

And what a delight it is. Dale Carnegie was an instructor of courses in effective speaking and human relations. With an enthusiastic and often flamboyant attitude, he explains how to win over people’s trust and hearts. Many anecdotes feature famous figures — Abraham Lincoln, Benjamin Franklin, and George Eastman of Kodak film, to name a few. The examples in which characters follow Dale’s suggestions often result in a successful transaction — whether it be a profitable contract or winning a political election. But this is not to say that the reader has to be in sales or politics to appreciate them.

These are stories about how people can make both someone else and themselves happy, how people make decisions based not so much on rationale but on emotions, and how you can be graceful in handling difficult situations with people.

The basic premise is that people need and crave the feeling of importance. And we can interact with people in a way such that they feel appreciated and important. Whoever practices these social interactions can be sure to be rewarded at the end by a lifelong friendship, a business deal, or a sales order, at least in the world portrayed by Mr. Carnegie.

The lessons — some examples being “give people sincere appreciation,”become genuinely interested in other people, and let them talk about themselves” — may be considered so uncontroversial as to be boring, but Dale Carnegie supplies ample “people stories” to make each one memorable and convincing.

Oh, and by the way, I like to hold up the cover high in the subway so that I can test whether people think I’m a loser. What’s rather disappointing is that hardly anyone seems to take notice. Oh well.

Filed under: books | Leave a Comment

Tags: "dale carnegie" "how to win friends" "reading" "commute"

Never Wrestle with a Pig

In a conversational style, Mark McCormack shares his bits of wisdom about managing a career and interacting with people. Reading through the pages feels as if I’ve dropped by his office for a chat. He suggests tons of examples from his own experience, and the anecdotes are convincing to his point.

Mark McCormack was a hugely successful and prolific person who founded the sports and entertainment management company, IMG. And I say this in the past tense because, it turns out that he passed away back in 2003! It’s an eerie feeling to be reading his book, mistakenly thinking that he’s talking to you directly, then finding out that he no longer exists in this world.

Anyhow, some of the pieces of advices I’ve dog-eared are these:

- You don’t need ten good reasons to make a decision

- Make a list of pros and cons, order them by importance and regard only the top two. This will help you be more decisive. We often forget to prioritize our lists, and paralyze our decision-making brains.

- Don’t let brainstorming kill your creativity

- Brainstorming puts a lot of pressure on people to come up with big ideas, which, in fact, don’t come by that often. It’s the little ideas that turn into something big, with the flexing of creative muscles at small milestones.

- Quote: “I’ve lowered my expectations. I’ve learned that you can’t expect yourself or your people to come up with big ideas all the time. Big ideas don’t come along that often. And even when they do, you probably don’t know it. The size and dimension of an idea– it’s big-ness— isn’t apparent until you act on it and see how it plays in the marketplace. Until then, it’s just an idea, no different from hundreds of other ideas. The key is to be creative in some way every day, to keep flexing the right muscles.”

I used to never read books written by sales people. I felt my designer/artist self being intimidated by what I assumed was a top-down attitude, where the unambiguous sales goal was to win. But, I realize there is more depth to the words of a sales guru. Mark McCormack obviously has a passion for life, for learning from past experiences, and an interest in the way people behave and interact.

The book is split into small chapters, so it’s good to read on the commuter train where you’re reading will be interrupted at the destination. Oh, and FYI the bold title on the cover will draw a lot of attention from passengers.

Filed under: books | Leave a Comment

Tags: "never wrestle with a pig" "management" "career management", business

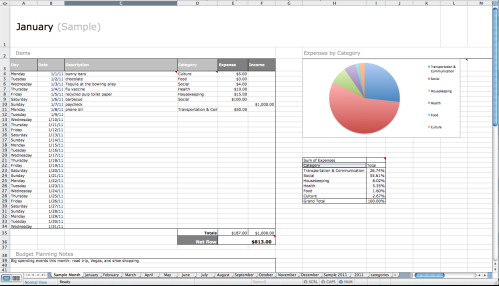

With 2011 coming around in two months, I’ve created an excel template to track expenses and incomes on a per-item basis. I’m sharing it in case you find it useful.

Click on the link to download the free .xslx file.

The features are pretty straightforward — the file is for simply logging all of your expenses and income item-by-item. You’ll need to have basic proficiency in Excel.

Let me step you through the parts of this Personal Expense Tracker.

1) Monthly Report: Each sheet in the document contains a month.

1-a) Log your expenses in this table.

1-b) Visualize where you spend heavily

1-c) Jot down things to keep in mind for the month.

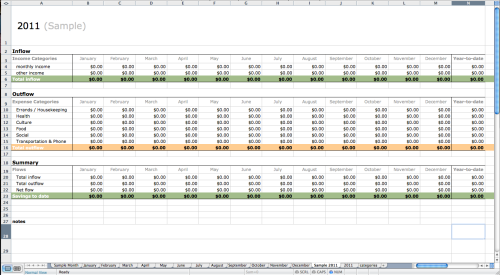

2) Yearly Report: Track the sum of your expenses and income.

This is an excel sheet, with no user friendly macros, so I’ll have to explain some of the details that take work to use.

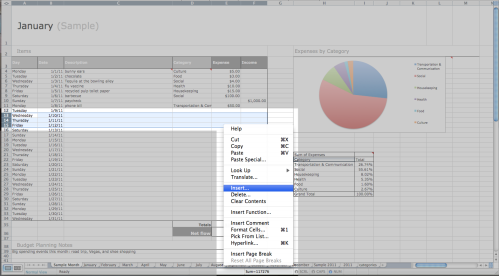

3) Add multiple items for one day

3-a) Add a row by selecting a row of cells below and right-click>Insert

3-b) Add multiple rows by selecting rows of cells below, and right-click>insert

4) Select a category for your expense.

Categories are defined in the “categories” tab.

5) Edit categories

5-a) Select the “categories” tab and edit the six keywords. Keep the number of items the same, or, keep reading on.

5-b) To change the # of categories, edit the cells, then Insert>Name>Define

In the “Refers to” box, specify the range of cells that contain your categories.

In the “Refers to” box, specify the range of cells that contain your categories.

6) Refresh data: Right-click anywhere on the table>Refresh Data

7) Roll over notes to see comments about this document

Filed under: project | 1 Comment

Tags: "excel template", "expense tracker", "personal expense", "personal finance", bookkeeping, excel, 가계부, ledger